Visual Teaching Guides and Video Presentations by University Teaching Staff: Analysis and Evaluation of an Innovative Experience

Guías docentes visuales y vídeo presentaciones del profesorado en la Universidad: análisis y evaluación de una experiencia innovadora

Laura Teruel Rodrígueza(*), María Sánchez Gonzálezb, Daniel López Álvarezc

a Departamento de Periodismo. Universidad de Málaga, España.

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7575-8401teruel@uma.es

b Departamento de Periodismo. Universidad de Málaga, España.

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3053-0646m.sanchezgonzalez@uma.es

c Servicios de enseñanza virtual y laboratorios tecnológicos, Universidad de Málaga, España.

http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1130-7780dlopez@uma.es

ABSTRACT

This article deals with the experience of an innovative educational and communicational project carried out by the Department of Journalism at the University of Malaga, Spain. This project aimed to develop audio-visual teaching guides and video presentations by the departmental teaching staff. To promote learning and replication, we describe its development and principal results and make a multidimensional evaluation based on observation, content analysis, and surveys involving interviews with the main participants and the target audience. Despite the unforeseen difficulty brought on by the pandemic, the balance drawn on the project’s usefulness is positive concerning both the online visibility and impact of the resources created, as well as the perceptions of the students and lecturers involved. Over two academic years, forty people – including technical personnel, trainee grant-holders and teaching staff – were coordinated to produce this didactic content, which has been viewed on YouTube by 2,800 people.

Keywords

innovation, audio-visual resources, journalism, student’s guide, YouTube, educational video

RESUMEN

Este artículo aborda la experiencia de un proyecto de innovación educativa y comunicacional puesto en marcha por el Departamento de Periodismo de la Universidad de Málaga, España, cuyo objetivo era desarrollar guías docentes audiovisuales y vídeo presentaciones del profesorado. Con la finalidad de promover el aprendizaje y la replicabilidad, se describe su desarrollo y sus principales resultados y se realiza una evaluación multidimensional de los mismos, basada en la observación, el análisis de contenido y el sondeo, mediante encuesta, a los principales participantes y destinatarios. Pese a la dificultad sobrevenida, fruto de la pandemia, el balance es positivo, tanto en lo referente a visibilidad e impacto en red de los recursos creados, como en cuanto a la percepción del alumnado y los docentes implicados acerca de su utilidad. Durante dos cursos, se ha coordinado a cuarenta miembros (entre personal técnico, becarios en formación y profesorado) para producir estos contenidos didácticos que han visualizado 2800 personas en Youtube.

Palabras clave

innovación, recursos audiovisuales, periodismo, guía del estudiante, Youtube, vídeo educativo

1. Introduction

Journalism studies, like so many other fields of study in today’s liquid society (Bauman, 2002), are necessarily dynamic; they are constantly being updated to adapt to the new realities of communication. We refer to updating in technical aspects (the use of new tools and social networks) and content (creation of new narratives and areas of specialisation) and how teaching/learning and the lecturer/student relationship are understood and conceived. In this sense, adapting to the student’s needs is essential by employing innovative methodological approaches and creating resources that support and guide digging closer to their consumer habits.

This is the spirit in which we have been working in the Department of Journalism at the University of Malaga (UMA), Spain. In 2019, our department celebrated the 25th anniversary of its foundation. Between 2019 and 2021, after being selected in an institutional call, we carried out the project “Curricular and teaching promotion via YouTube. Design and dissemination of audio-visual teaching guides and video presentations by the teaching staff in Journalism”.1 This was a continuation of, and improvement on, an earlier project carried out between 2017 and 2019 (17-083: The use of YouTube for promoting the curriculum. Design and dissemination of audio-visual teaching guides in Journalism). In that first initiative, audio-visual guides were developed for the optional subjects of the UMA’s Journalism Degree. We are therefore talking about four years of innovative experiences in the Department, carried out in a coordinated way.

In the project analysed in this article, the aim was, firstly, to extend and develop the production of guides to the compulsory subjects of the Journalism Degree and, secondly, to explore new formats of visual communication through the creation of video presentations by the teaching staff in the form of visual elevator pitches.

The underlying objective is to inform students dynamically and transparently, using an audio-visual language familiar to them, and to showcase the Department’s curriculum and human capital and, consequently, the University itself by increasing their visibility. Audio-visual narration forms part of the content and skills that are acquired through those studies, which is why the proposed project is, in addition, coherent with the field’s epistemology.

To contribute some keys that favour its replication in other contexts and thus foster innovation, the present article explains the proposal that guided this experience and analyses the results, paying attention to both the content generated and the perceptions of the project’s leading actors, namely, the participating lecturers and technicians on one side, and the students studying for the UMA’s Journalism Degree on the other. How this multidisciplinary collaborative initiative was developed over several academic years and the evaluation of its results using its target audience provide it with the comprehensive scope and vision required by innovative educational projects.

2. Video as an Educational Resource

For decades, video and multimedia content have been successfully employed as tools for teaching/learning in diverse fields and educational levels, including the university (Zabalza et al., 2017). However, the worldwide COVID-19 pandemic and the resulting tactical viralisation of teaching in 2020-2021 have increased their use. In this context, their importance has been confirmed for guidance, motivation, active learning, acquiring skills, improving student performance (De la Fuente et al., 2018), and telematics.

The use of social media in general for academic ends increased during the pandemic (León- Gómez et al., 2021). Amongst these media, as Chávez Ramos et al. (2021) note, “it became evident that YouTube has become a perfect setting for teachers, as it is a source that motivates a multidisciplinary audio-visual orientation in students”, and this has given rise to “a new generation of teacher and student prosumers in the elaboration of thematic audio-visual content” (p.1). In Social Sciences, its potential as an archive of educational videos and a space for student creation makes it an outstanding information and communication technology (ICT) tool for teaching staff (Lozano Díaz et al., 2020).

This success is due, amongst other reasons, to the multimedia and audio-visual nature of these videos, which foster a more attractive communication and a better understanding of the content than merely textual material, and to their potential for harmonising teaching-learning experiences and bringing lecturers closer to students utilising their voice or image (Sánchez González, 2021). With the possibility of incorporating interactive or hypermedia options, subtitles and other resources to enrich them, videos also emerge as participatory and accessible resources that can be viewed in a personalised way at any time, and students can thus learn anywhere and at their own pace (Sánchez González, 2021).

As many are digital residents, cultural and consumer reasons for university students must be added (White, 2011). That is, they spend part of their lives online, consuming digital visual and multimedia content on different audio-visual platforms on social media. Amongst these, the now well-established YouTube and other emergent media like TikTok or Twitch concentrate a growing number of users who spend a considerable part of their time each day surfing these media – somewhat over one-third of their users spend more than an hour a day, according to data from 22 March 2022, extracted from the 24ª Edición de Navegantes en la Red (24th Edition of Web Surfers) (AIMC, 2022).

Different studies show that it is precisely these channels that many young people have been using in recent years when making critical decisions, such as choosing a university. Consequently, many referential international centres, like MIT or Oxford University at first2, two and more recently, most university institutions, including Spanish ones, dedicate part of their energies to producing and disseminating informational and educational audio-visuals for these channels.

With these and other references, in the framework of the Educational Innovation Project (EIP), the video guides were conceived as a short version – and therefore “more ‘humanised’, attractive and adapted to the potential of online communication – of the teaching guides, which stress the basic information and strengths of a course (why to do it, what it proposes, skills/opportunities for work, teaching staff” (Sánchez González, 2021, p. 211). In this way and depending on the context, tone and message, these resources can fulfil “a triple function (didactic-educational; informational; and promotional)” (Sánchez González, 2021) concerning programs and subjects. In the framework of this initiative, these resources consisted of brief multimedia informational content that synthesised and complemented the academic programming of the optional subjects, making them more accessible and easier for students to consume (Teruel-Rodríguez et al., 2018).

The results of the earlier experience involving video guides (Teruel-Rodríguez & Sedano, 2020) and related innovative educational projects within the same Faculty (Teruel-Rodríguez et al., 2023) or, concretely, experiences focused on the development of multimedia content in Communication Sciences (Monedero et al., 2020) make the didactic potential of this initiative clear.

3. Objectives

The general objectives of this article are to spread and analyse innovative teaching strategies involving the use of ICT in the university field. Secondly, to provide a comprehensive description of the work process – from the initial conception to the evaluation of results – of a successful case of university innovation to favour its replication. Finally, it proposes to reflect on the need to introduce social media and multimedia content as educational resources linked to Degree Courses in Communications, primarily based on expanding the use of ICT during the pandemic in a context where. Moreover, students spend part of their lives online.

As noted above, in the following pages, we focus on analysing one case: concretely, a university's innovative educational project arising from an institutional initiative linked to studies in Communication Sciences (Journalism) of a Spanish public university (Malaga). The main goals of this project were:

• Promote reflection on ICT as an instrument at the service of innovative methodologies.

• Stimulate and support the continuity of the consolidated innovative teaching group to give solidity and depth to this project.

• Implement new pedagogical commitments connected to the media consumption habits of students.

• Provide students with prior knowledge of the subjects, creating realistic expectations about their content.

• Showcase the Department and the University's human capital, both teaching and technical.

4. Method

4.1. Methodological principles

A series of premises developed the innovative educational project on which this article focuses:

• Prior diagnosis. Amongst the reasons leading us to propose the project, four can be underscored: (1) the media consumption habits of the Degree Course students we are addressing, for whom video forms part of their everyday life; (2) being coherent with our field, Communications, making use of its formats and techniques to spread the curriculum and introduce the teaching staff; (3) the possibility of exploiting the human capital and technical means available in the Department and the Communications Faculty itself, which has young and dynamic personnel and good technical resources; and (4) the need to open up new channels for lecturer-student collaboration and also foster basic digital skills in both groups.

• Strategic planning of innovation. Under the direction of two lecturers from the Department of Journalism who acted as project coordinators3 and based on previously set objectives, two main phases of development were proposed, focusing on elaborating visual guides to subjects and lecturers’ video presentations, respectively. To complete the project, a system of evaluation and improvement was designed that, in addition to its direct results, also considers the project’s effect on students and lecturers, as we will describe further. While the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic forced us to adapt the initial chronogram and approach, having this prior planning available facilitated tactical decision-making. Similarly, the evaluation made it possible to orientate the results towards continuous improvement and evaluate potential future approaches for projects.

• Collaboration between different professional categories. Together with nearly 30 members of the Department of Journalism (lecturers), audio-visual and virtual teaching technicians and lecturers from other fields, they have also improved the quality of the results.

• Student viewpoint. At every moment, we had the help of trainee students in the department to record, voice-over, and post-produce the videos. As noted above, we also gathered the evaluation of the results by students studying for the Degree Course in Journalism and the possible influence of the videos on these students.

• Heuristic evaluation. Once the project had been developed, and in keeping with the viewpoint of the experts on educational innovation (Marcelo, 2011, 2022), a critical analysis was made that included both the objective indicators linked to the content and resources developed and evidence of the use made of them by the main agents involved, lecturers and students, as well as their perception of the results. Furthermore, the project’s coordinating team made a self-criticism of these results and proposals for future improvements.

4.2. Development of the project: phases and approach

Phase 1. Visual guides

The audio-visual guides’ production is based on a model established in the earlier project, which enabled us to estimate that it would be possible to make ten new ones each academic year. The earlier work had been published on the UMA Journalism channel on YouTube.

Eight recordings were made during the first semester (2019-2020) and edited in the following months, while material was collected on other subjects, which were to be supplemented later. We had a highly skilled team on hand, formed of grant-holders who were collaborating with the Department; they were integrated into the project and received training to help them in their work, provided as part of the project itself. A practical face-to-face course was organised in which several EIP teachers trained the rest of the members on technical aspects, digital narration author’s rights concerning external resources, and work processes in the innovative project. This training was also considered essential for establishing the flow of work and the final coordination process, overseen by one of the coordinators in line with what had been learned in the previous experience (Teruel-Rodríguez & Sedano, 2020). We continued working with a technician from outside the University who had experience in educational audio-visual content and was contracted to do the final editing.

Our starting point was an assessed and completed video model, which had been previously viewed and shared by the entire teaching staff. The types of shots, the editing template, the sound effects, and the kind of voice-over were all approved. The team of student collaborators coordinated with the participating lecturers in making the recordings and correcting the script that was read out and the phrases that were projected on the screen to make them accessible. The aim was for the videos to be short (between two and three minutes duration), dynamic (a succession of shots lasting no more than fifteen seconds), homogeneous and elegant (based on a design template), and informative. For this purpose, consensus was reached with the lecturers about which shots to include on each subject, and an essential list of questions was designed with the recommendation that they should be answered in the voice-over. It was suggested that the following 12 questions should be answered:

• Greetings and presentation of the subject (Year and semester in which it is taught).

• Definition of the subject.

• What relation does it have to the journalistic profession's context and other subjects in the study plan?

• What prior knowledge is it recommendable for students to have?

• Why should the students study the subject? (Especially about optional subjects).

• What will students on the course be studying? The essential content of the teaching guide.

• What are the objectives of the subject?

• What skills will students acquire by doing the course?

• What types of practical training are carried out?

• What form does the evaluation take?

• What professional openings does the subject facilitate?

• What are the responsibilities/tasks of students who choose this subject?

• Farewell, complementary information, links…

Recording the videos of those subjects, which were still pending from the earlier period, should have begun in March 2020, but the pandemic arrived. COVID-19 brought the virtualisation of teaching and, later, the bimodal style of classes. The decision was therefore made to put the audio-visual guides project on hold for both image and health reasons: the idea was that they should extend beyond that year and be representative of face-to-face teaching under normal conditions. Even so, work continued, and in January 2021, the vocal parts of the pending subjects were recorded. From the middle of that year onwards, the videos were made and corrected, and permission was arranged with RTVE (Radio Televisión Española) for certain inserted shots. Special care was taken throughout this process to respect the property rights of images and music; in the case of resources belonging to the University of Malaga, these rights had been arranged previously. Except for one video, which had to be revised during the summer, from July onwards, all the lecturers had their videos ready for inclusion in their subject’s space on the virtual campus. Thus, by the start of the academic year in September, all of them had been uploaded to the UMA Journalism channel on YouTube.

Phase 2. Lecturers’ video presentations

This second phase is the novelty of this project, which meant that efforts had to be focused on exploring possibilities and formats and creating valid, effective, and efficient prototypes and models. That is, the aim was that the latter should fulfil the communication objectives proposed and that production should be viable from the technical and teaching point of view with the resources available and within the deadlines set for the project. But it was also necessary that they should be sustainable – i.e. not require constant updating – and could be extrapolated beyond the pilots produced in this project (whose production times were altered by the Covid-19 pandemic) for the production of other videos in the future, both by the Department of Journalism and by others that might want to “appropriate” and import the model.

This work was developed in 2021, during the final stage of the project, and throughout the process, the coordinators worked closely and collaboratively with the technical personnel. It began at the start of the year with the search and analysis of good practices and inspiring examples of videos (benchmarking), brainstorming and testing possible formulas and models concerning the structure of the videos, content, types of shots, duration, graphic design, etc.

To guarantee the structural homogeneity of the videos and facilitate their preparation for the lecturers, several questions were designed that would later be put directly to the lecturer in the form of a video interview:

1. Who are you? Introduce yourself with a phrase and explain how you define yourself as a person and/or an academic and, where applicable, as a professional (think up a word that summarises your trajectory/personal brand in the form of a slogan/initial hook).

2. When have you been in the department? And, what does your teaching focus on (type of subjects, fields of specialisation…)?

3. How would you describe your classes? What do you think students take away from them? (Reinforcing the previous question a little).

4. What is your trajectory as a researcher? What are your achievements? What motivates you?

5. What else do you do, both in and outside the Department and the University? Tell us a little about what’s most outstanding.

6. What do you think the preceding contributes to your teaching and research work, and vice versa?

7. What were your main professional learning experiences, and what would you share with your students and colleagues? (tips on job orientation).

8. How do you think your students view you? What do you think they most value in your classes? And your colleagues?

Parallel to this, a series of common graphic and audio-visual resources were developed to standardise the appearance of the videos (opening bumpers, typographic and vector models, credits page…). Additionally, the production of the videos was planned. It was decided that the recordings would be done in the Faculty’s studio against a white background to facilitate the insertion of supporting texts and audio-visual resources; two cameras would be used, one for close-up/medium close-up shots and the other for extreme close-up shots; and one person behind the camera would put questions to the interviewee, who would be looking directly towards them and not at the camera, etc.

In June 2021, two pilot videos were recorded with one of the coordinators:

1) Video interview lasting some 10-15 minutes, longer and more dialogic/reflexive than the short version of the lecturer’s presentation video, with separating screens on which the written questions appear, and including personalised audio-visual resources (for example, video fragments of activity or video captures) inserted on a small screen. In contrast, depending on the case, the teacher’s image continues to be seen or occupies the entire screen with the latter’s voice off. Also, some extra shots of the Faculty recorded with the lecturer were added. Additionally, in the final part there are several testimonies, in written and audio-visual format, of students and former students (who give their opinions on the interviewee’s qualities as a teacher…)

2) The short version of the lecturer’s presentation video lasts 3-4 minutes in the form of a talk or testimony delivered against a background of shots similar to those in the long video. In this case, no interviewer is asked the questions. Instead, the lecturer provides a kind of sales pitch that is somewhat longer than usual without looking directly at the camera, following a guiding thread, with supporting texts added in the editing. In this respect, it is midway between an elevator pitch and a typical interview. Extra shots recorded in the faculty are also added at the beginning, middle, and end.

Both models were then edited, with the insertion of standard graphic designs, texts supporting the lecturer’s talk (in this respect, imitating the model of the visual guides and increasing the accessibility of the videos), and fragments of videos linked to the academic or professional trajectory of the lecturer, supplied by the latter. Concerning the two models, the first (the video interview), although it was the initial idea, was seen to be very long in terms of time and consumed many resources, not only in post-production but also on the part of the interviewee, as they had to search for and select resources (which, moreover, were not always of the required technical quality, and it was also necessary to prepare a detailed technical guide with indications for editing…). Therefore, it was decided to produce a model closer to the second. Facing the possibility that not all of the lecturers would have the supporting audio-visual resources available or that this would delay production, it was decided to record supporting shots in situ, in the faculty itself, with the lecturers as their protagonists, “in context”, with which to enrich the videos.

At the same time, besides preparing prototypes for the videos, it was considered essential to establish the procedure for their production, to which end a guide was prepared for the participating lecturers. Besides explaining the process, this guide includes patterns and models to facilitate the preparation of their video interviews and thus speed up the recording and subsequent editing phases.

From that point on, in October 2021, a group of Journalism lecturers were contacted. Although a few (4 people) were given deadlines, they were diversified in terms of their fields of specialisation. They were invited to participate in producing the shortened version of their presentation videos. The recording of these videos and the corresponding extra shots took place in October and November 2021. As noted above, they all followed the second of the initial pilot models (the short version of the presentation videos). However, their duration was somewhat longer than the initial six minutes per video. This process was concluded with their editing between November and December of the same year, supervised by the EIP coordinators and the protagonists, and they were published on the UMA Journalism channel on YouTube.

4.3. System of evaluating results

Four basic indicators were considered when evaluating the project’s scope. The first two concern the results about the participating lecturers (as their participation was voluntary) and the number of videos produced, aiming to cover at least 80% of the compulsory subjects in the case of the video guides and making a pilot of 4-5 lecturers’ presentation videos. In relative terms, the other two indicators refer to the visibility of the online resources (data for viewings on YouTube) and the perception of the project’s impact on the primary target audience.

To cover this latter aspect, once the project had been executed, two online surveys were designed and distributed between January and March 2002, following a pre-test, to Degree Course students and lecturers in the Department of Journalism. Both include items that cover evaluative dimensions of the innovative project that are essentially personal (attitudes, perceptions, involvement, satisfaction, etc.) and also organisational (for example, evaluating the project’s dissemination) (Marcelo, 2022). In designing the survey, we also considered the model used by the University of Malaga, agreed by consensus with the rest of the Andalusian universities and the Directorate for Evaluation and Accreditation – Andalusian Knowledge Agency (DEVA – AAC), to gauge the opinion of the students based on Likert scales. This model was adapted according to the aims of this research.

The survey addressed to the teaching staff first asked questions aimed at assessing the degree of knowledge of the guides, whether they had shared them and whether they considered them useful for their different objectives—the second part aimed to evaluate the formal and content aspects. Finally, a free-format section was included for recommendations and comments. The survey was provided through the distribution list and personal contacts between February and March 2022.

For its part, the questionnaire for the students was delivered on similar dates, with the support of the lecturers who teach different subjects in the Journalism Degree to guarantee the diversity of the sample. Besides being aimed at the most recent class (2018-2022), who were studying their 4th year then, it was sent via the virtual campus to previous courses with access to the guides. In this way, we sought to obtain a stratified sample and, with the survey’s dissemination through the chats of the class groups (using messaging apps like WhatsApp or Telegram), to facilitate a snowball effect. In this case, the questions were designed to evaluate the students’ knowledge of the videos (whether they knew about them or not and how they had accessed them) or their perception of their content, form, and usefulness as a resource for guidance. To complement this, they were also asked to evaluate the potential of the lecturers’ presentation videos according to different criteria. Since the latter is a resource that has only recently been introduced, it was assumed that this group would be even less familiar with them.

5. Results

5.1. Videos produced

It was possible to make 8 video guides in this project, which are now added to the 12 produced in the previous project (2017-2019). The results are available on the YouTube profile created by the Department of Journalism on the 25th anniversary of its creation at the University of Malaga and on its website. The videos were also made available to the lecturers so they could use them directly. Thus, several distribution channels have been set up. These multimedia products follow the model explained in earlier sections (Figure 1). They follow the same patterns to ensure that they have a dynamic quality and that the informational content predominates. They were produced by technical personnel, both internal and externally contracted, supervised by the teaching staff and the project coordinators.

Figure 1. Collection of video guides of the Department of Journalism UMA on YouTube.

Concerning the lecturers’ presentation videos, it was also possible to produce and publish 5 of these on YouTube (see image below); despite the changes in the plan due to the pandemic, these included lecturers with different academic profiles. This made it possible to validate the viability of the standards defined for fulfilling the objectives proposed, irrespective of their field of specialisation, as well as their flexibility so that each lecturer could choose what to emphasise and how to present it. In this respect, they received constant support from the EIP team, which was present at all the recording sessions to guarantee a certain degree of homogeneity.

The identifying features of the model were defined: testimonies based on several critical questions put to the lecturer; the lecturer as narrator in front of the camera but without reading or looking directly at it; rigorous content but with an accessible and somewhat “relaxed” style; dynamic format, with alternating close-up and supporting shots; a minimalist appearance, recorded in the studio with two cameras, using supporting textual captions and where relevant video resources to underscore the main ideas; brief duration; etc.

Figure 2. Distribution list for “PeriodismoUMA: vídeo presentaciones docentes” (UMA Department of Journalism: lecturers’ presentation videos) on YouTube.

Together with the videos, different resources useful to the Department’s lecturers were generated. In addition to the “Guide for the production of visual guides to subjects”, which emerged from the workshop held in October 2019, another titled “Lecturers’ video presentations. Guide for teaching staff participating in the recordings” was elaborated at the end of 2021. These resources, besides systematising and facilitating the lecturers’ participation in EIP, fostered training in digital skills (searching for and selecting information, screenplay writing, communication facing the camera) and were intended to contribute to “exporting” the creation of video guides and lecturers’ video presentations to other Departments.

All content elaborated (guides and video presentations) is available for consultation online, not only by the teaching staff but also by the university community and society in general, under licence from Creative Commons, which encourages its use and reuse.

5.2. Online visibility of the videos

According to the data provided by the YouTube platform, the average time spent watching the video guides to subjects is 1:03 minutes, and for the lecturers’ video presentations, it is 2:02 minutes. These initial data strengthen the importance of concise and brief audio-visual resources. By sex, 70.4% of the viewings were made by women.

Concerning the sources of the traffic generated by these videos, 26.5% proceeds from external sources: websites and applications that link to this content. Of this figure, 29.1% accessed the videos from www.uma.es; that is, videos housed on the departmental website or the virtual campus. The second access source is Twitter, with 15.8%, followed by WhatsApp (10.6%) and Facebook (8.7%). All of this underscores the importance of using the teaching potential of social media.

Surfing via the profile of PeriodismoUMA (Journalism UMA) on YouTube is the source of accessing 26.2% of the videos and distribution lists created on that website, which are, in turn, responsible for 11.5% of the viewings. Direct searches for these resources on YouTube account for 15.4% of access.

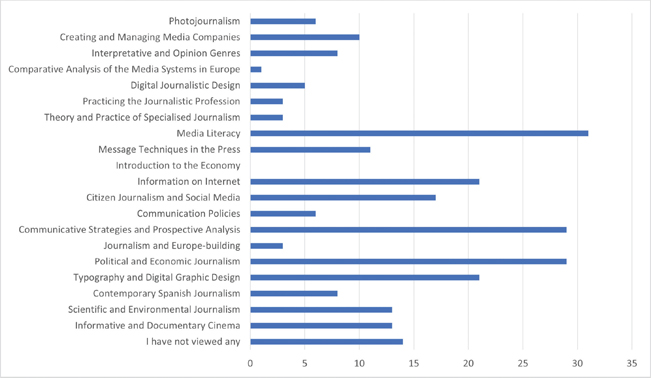

The data on consumption, extracted on 28 March 2022, show over 2,800 viewings across all the resources realised in the framework of the EIP. Amongst the video guides to subjects, it is worth highlighting that the upper part of Table 1 is occupied by resources produced in the project's first phase. In turn, these are optional subjects that the students must choose from. The survey analysis conducted with students emphasises that they found the videos helpful. While the five lecturers’ presentation videos accumulated 172 viewings, this lower impact is explained by the fact that they were posted more recently (a mere three months online at the time of collecting the data, March 2022).

Table 1. Viewings of the guides to subjects. Date of analysis: 28/03/2022.

Subject |

Number of viewings 28/03/2022 |

Communicative Strategies and Prospective Analysis |

383 |

Political and Economic Journalism |

293 |

Media Literacy |

274 |

Creating and Managing Media Companies |

217 |

Citizen Journalism and Social Media |

204 |

Typography and Digital Graphic Design |

187 |

Photojournalism |

185 |

Information on Internet |

184 |

Scientific and Environmental Journalism |

158 |

Interpretative and Opinion Genres |

144 |

Journalism and Europe-building |

137 |

Comparative Analysis of the Media Systems in Europe |

97 |

Message Techniques in the Press |

43 |

Informative and Documentary Cinema |

31 |

Contemporary Spanish Journalism |

29 |

Theory and Practice of Specialised Journalism |

20 |

Practicing the Journalistic Profession |

20 |

Communication Policies |

12 |

Digital Journalistic Design |

9 |

Introduction to the Economy |

3 |

TOTAL |

2630 |

Note: YouTube.

5.3. The students’ perception

The survey conducted with the student classes from 2016/2020 to 2021/2025 was obtained in February 2022 via the virtual campus of different subjects. Close to 100 answers (91) were received, most of which were from the two most recent classes (over half, 56%, from 2018/2022 and 22% from 2017/2021).

It could be observed that 65.9% of the students knew about the existence of the video guides. 58.8% stated that they had viewed them through the space assigned to each subject on the virtual campus, while 35.3% accessed them directly through their lecturers, who showed them in the classroom. Their classmates informed the interviewees about them in 10.3% of the cases.

As can be seen in Figure 3, the subject “Media Literacy”, with 34.1%, obtained the highest number of viewings, closely followed by “Political and Economic Journalism” and “Communicative Strategies and Prospective Analysis”, both with 31.9%. The subjects in these three cases are optional. 15.4% of the sample replied that they had not seen any of these productions.

Figure 3. Number of viewings of the different video guides to subjects according to the student survey.

Note: Elaborated by the authors.

For the videos’ usefulness, 63.8% of the students stated that they are helpful or handy for learning about subjects and, in the case of optional ones, for being able to choose amongst them when enrolling.

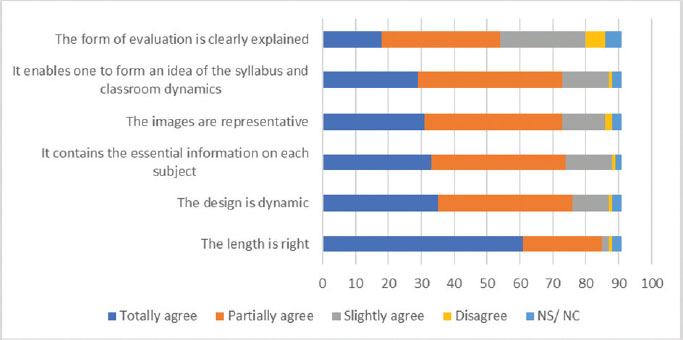

Concerning the content and design of the videos (Figure 4), it could be seen that 55.5% agreed that their duration was correct. In comparison, 31.8% agreed that the pieces' design was dynamic. 67% partially or decided that the pieces contained the essential information on each subject. 66.4% considered that the images were representative and that the content enabled them to form a clear idea of the syllabus and classroom dynamics of the subjects. 47.3% partially or agreed that the form of evaluation was clearly explained.

Figure 4. Evaluation of Contents. Survey of Students.

Note: Elaborated by the authors.

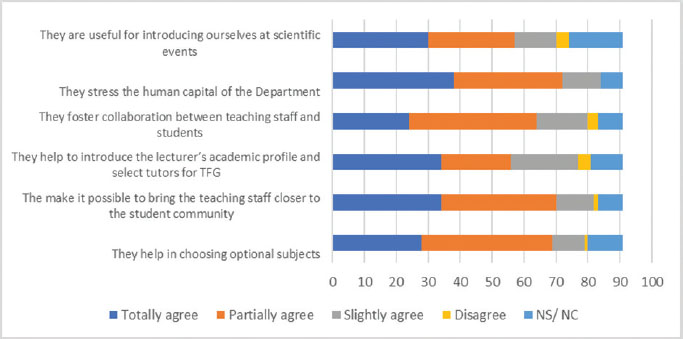

In the final place, they evaluated the potential of the video presentation to bring the teaching staff closer to students, selecting optional subjects and showcasing the importance of the Department’s human capital (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Utility of the videos. Survey of students.

Note: Elaborated by the authors.

5.4. The experience of the teaching staff

The virtual survey in the Department of Journalism was conducted between February and March 2022, when it was made up of 40 members, divided between Teaching and Research Personnel and Trainee Research Personnel. From this figure, 16 replies were received, which is considered significant as they proceeded from different academic and professional specialisation areas.

The results showed that 68.8% used these resources in class, 31.3% said they employed them regularly and 37.5% punctually or sporadically. We asked those who had used the video guides which channel they had hired to spread them amongst the students. A large part (50%) used them at the initial meeting organised by the degree coordinators with third- and fourth-year students to present the optional subjects before enrolling. The other most frequent options are uploading them to the spaces of their subjects on the virtual campus and showing them in class at the start of the semester, both with 28%.

The usefulness of these resources to learn about subjects and to enable students to choose amongst them when enrolling for optional subjects was underscored by the maximum scores on the scale of 93.8% of the replies. The lecturers endorsed the usefulness of these videos but circumscribed this to the teaching field. Only 18.8% said they have employed them for research or informative purposes at congresses, as against 75% who have used them in class.

Asked about the effort required in making these videos, we found a total division between those who considered that they had involved very little or too much work, as the replies were shared uniformly on the scale of options.

Figure 6 provides detailed answers to an item consisting of several indicators. The aim was to evaluate the content and design of the videos. Amongst the formal aspects, duration and dynamism are valued optimally, while there is room to improve the representativeness of the images. Concerning content, they are considered to contain and highlight what is essential to each subject and – on these points, there is less but still considerable agreement – that they make it possible to form an idea of the classroom dynamics and the form of evaluation.

Figure 6. Evaluation of the video quality according to the student survey.

Note: Elaborated by the authors.

The survey included an open question to register qualitative values as well. Amongst the answers given, it was possible to observe an expression of thanks for coordinating the innovative educational project and the supervision of the videos. Amongst the recommendations, there were proposals to include the opinion of students who have completed the course and to try and commit the teaching staff to use the video guides and thus increase their dissemination not only amongst the target audience but also amongst the latter’s families. Regarding the formal aspects, there were suggestions to accelerate the rhythm and use keywords in the narratives to make them more attractive to the younger public.

Concerning the lecturers’ evaluation of the video presentations (the second part of the questionnaire), it can be seen in Figure 7 that the majority opinion was in total agreement concerning the usefulness of these videos in encouraging collaboration between the teaching staff and taking the latter closer to the student community. There was partial agreement that they could help disseminate the lecturers’ profiles among students.

Figure 7. Results about the utility of the videos were obtained from a survey of lecturers.

Note: Elaborated by the authors.

Finally, when asked whether they would like us to make lecturers’ presentation videos for them in future project editions, 43.8% of the teaching staff answered in the affirmative.

6. Conclusions

The primary purpose of writing this article is to spread and analyse innovative teaching strategies in the university area involving ICT. Related to this, one of the general aims is to reflect on the need to introduce social media and multimedia content as educational resources linked to Communications Studies or the Journalism Degree, especially in light of the situation generated by the pandemic. Based on our experience, the balance we draw is a positive one. Pérez Tornero and Varis (2012) argue that in the setting of the society of “information overload”, there has been a transformation of the profile of the student body, which must be considered for the task of teaching, and which has played a defining role in the latter’s viralisation. This generation needs to have the option of receiving and sending multimedia messages and communicating in this complete and continuous way. We believe that our project is directly rooted in this conception of the potential of videos in education.

Similarly, to facilitate replication, we aimed to provide a complete description of the work process, from the initial conception to the evaluation of results. In our opinion, this initiative, as yet unfinished, evinces the need to avail oneself of long-term institutional support when undertaking ambitious projects such as this. The implantation of any innovation process requires, amongst other factors, the support of the bodies that organise and design the educational systems, as well as a continuous effort on the part of the teaching staff (Marcelo, 2016). This author holds that material and organisational conditions must be created for this to happen. Still, the initiative must always proceed from the teaching staff, who must be motivated to innovate. Thus, it is essential to have available academic infrastructure and budgetary resources that enable the purchase of material and the hiring of technical personnel, in this case, to finalise the editing and voice-over processes professionally. In addition, we raised the need to evaluate the innovative project regarding both the process and the results (Marcelo, 2016). Based on the difficulties and results of earlier phases, continuous learning and the final evaluation were basic premises (Teruel-Rodríguez & Sedano, 2020).

The goals sought in the innovative project analysed here have been met, especially the idea of providing the students with prior knowledge about subjects and creating realistic expectations about their content. The video guides have received over 2,600 viewings registered on YouTube since these initiatives began (over 2,800 with the lecturers’ presentations). 65.9% of the Journalism students say that they have watched them. Concerning how they were perceived, a similar percentage of students consider that they have been helpful or instrumental in gaining prior knowledge about the subjects they would study. For their part, the Department’s teaching staff were even more satisfied with the result of the videos, and practically all of them (93.8%) awarded maximum scores on the scale considering their usefulness for introducing the subjects they teach.

The unexpected circumstances brought on by the pandemic have undoubtedly conditioned the results, limiting production from the quantitative point of view, especially for the lecturers’ video presentations. Despite that, the experience of the group that recorded them, which defined them as the teaching staff’s “hidden curriculum”, also endorsed the results obtained in the surveys of lecturers and students. In short, we can say that these presentations, like the video guides, also fulfil our vision: humanising and personalising teaching and bringing lecturers closer to students in the Department of Journalism at the UMA.

Concerning their limitations, it should be mentioned that the prior training given to the teaching staff helped develop this initiative, which could pose a difficulty in other fields. Audio-visual narration is a discipline in which training is required, so it is worth recommending that professional advice be sought when replicating this proposal. Another limitation that should be noted concerns the project’s continuity or capacity for adaptation: updating the video resources to respond to the unique needs of the student body or to reflect possible changes in the teaching program proves difficult. Most subjects that form part of this project have accumulated a long teaching trajectory. Still, if there should be changes in the study plan – something necessary to guarantee the dynamism of university teaching – it is essential to create protocols for updating the multimedia material produced.

Finally, the experience has evinced the university’s enormous capacity for adaptation in response to challenges of educational innovation and other aspects of teaching and innovation. Similarly, we consider that a multimedia production has been achieved that showcases the human capital of the Department and the University, both teaching and technical. Coherent results have been obtained regarding quality audio-visual products concerning the teaching spirit and the content taught in Journalism in Communications Sciences (Pérez Tornero & Tejedor Calvo, 2016). Moreover, this has been an enormous learning experience involving optimised and systematised processes, and it has been thoroughly documented, which favours its future replication by other teams both within and beyond the Department and the University.

Authors’ contribution

Laura Teruel-Rodríguez: Conceptualisation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Fund acquisition, Research, Methodology, Supervision, Visualization, Original draft, Drafting - review and editing.

María Sánchez-González: Conceptualisation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Fund acquisition, Research, Methodology, Visualization, Original draft, Drafting - review and editing.

Daniel López-Álvarez: Data curation, Methodology, Visualization, Original draft.

References

AIMC. (2022, March 10). Teletrabajo, criptomonedas, TikTok, Bizum y el 5G, principales tendencias digitales de 2021 en España. Asociación para la Investigación de Medios de Comunicación. Retrieved June 1, 2022, from https://d66z.short.gy/JsJ4Ai

Bauman, Z. (2002): Modernidad líquida. Fondo de Cultura Económica.

Chávez Ramos, L. A., Hualpa Flores, A. M. del C., Luis Paredes, E., & Vásquez Condezo, E. H. (2021). Importance of Audiovisual Resources in Teacher and Students During the Covid-19 Pandemic. Religación. Revista De Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades, 6(30), e210833. https://doi.org/10.46652/rgn.v6i30.833

De la Fuente Sánchez, D., Hernández Solís, M., & Pra Martos, I. (2018). Vídeo educativo y rendimiento académico en la enseñanza superior a distancia. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación a Distancia, 21(1), 323-341. https://doi.org/10.5944/ried.21.1.18326D

León-Gómez, A., Gil-Fernández, R., & Calderón-Garrido, D. (2021). Influence of COVID on the educational use of Social Media by students of Teaching Degrees. Education in the Knowledge Society, 22, e23623. https://doi.org/10.14201/eks.23623

Lozano Díaz, A., González Moreno, M. J., & Cuenca Piqueras, C. (2020). YouTube como recurso didáctico en la Universidad. EDMETIC, 9(2), 159-180. https://doi.org/10.21071/edmetic.v9i2.12051

Marcelo, C. (2011). Estudio de campo sobre la innovación educativa en los centros escolares". In: Ministerio de Educación. Secretaría de Estado y Educación Profesional. Instituto de Formación del Profesorado, Investigación e Innovación Educativa (ed.), Estudio sobre la innovación educativa en España (pp. 736-930). Ministerio de Educación Cultura y Deporte, Subdirección General de Documentación y Publicaciones.

Marcelo, C. (2016). La innovación en la universidad: del Gatopardo al IPhone. Revista de Gestión de la Innovación en Educación Superior REGIES, 1, 29-57.

Marcelo, C. (2022). Desarrollo, evaluación y difusión de proyectos de innovación: claves prácticas. In Área de Innovación (2022). Programa de #webinarsUNIA. Plan de Formación de Profesorado de la UNIA de 2022-23. http://hdl.handle.net/10334/6235 (recording and presentation)

Monedero, C. R., Pulla, G. L., & Mercado, M.T. (2020). Una propuesta para el uso de píldoras audiovisuales en la presentación de asignaturas de Ciencias de la Comunicación. F. J. Ruiz, N. Quero, M. Cebrián, & P. Hernández (Eds.), Tecnologías emergentes y estilos de aprendizaje para la enseñanza (pp. 174-187). Junta de Andalucía.

Pérez Tornero, J. M., & Tejedor Calvo, S. (2016). Ideas para aprender a aprender: manual de innovación educativa y tecnología. Editorial UOC.

Pérez Tornero, J. M., & Varis, T. (2012). Alfabetización mediática y nuevo humanismo. UOC

Sánchez González, M. (2021). Vídeos (y pódcasts): posibilidades, formatos y claves de producción. In M. Sánchez González (Ed.). #Dienlínea UNIA: guía para una docencia innovadora en red (pp. 208-225). Universidad Internacional de Andalucía. https://doi.org/10.56451/10334/6116

Teruel-Rodríguez, L., Martín Martín, F. M., & Palomo Torres, M. B. (2018). El uso de YouTube para la promoción curricular. Diseño y difusión de guías docentes audiovisuales en periodismo. In I Congreso Virtual Internacional de Innovación Docente Universitaria. Universidad de Córdoba. Retrieved from: https://d66z.short.gy/VU4Yqt

Teruel-Rodríguez, L., & Sedano, J. (2020). YouTtube, un aliado para trazar el itinerario curricular: experiencia de innovación educativa en el Grado de Periodismo. In Alfabetizando digitalmente para la nueva docencia (pp. 397-408). Pirámides, Grupo Anaya.

Teruel-Rodríguez, L., Sedano, J., & Montiel Torres, M. F. (2023). Estrategias para virtualizar la docencia universitaria en el Grado de Periodismo: innovación y evaluación de resultados en el estudiantado. In S. Tejedor, & C. Pulido (Eds.), Nuevos y viejos desafíos del periodismo (pp. 35-54). Tirant lo Blanch.

White, D. S. (2011). Visitors and Residents: A new typology for online engagement. First Monday, 16(9). https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v16i9.3171

Zabalza, I., Peña, B., Llera, E. M., Usón, S., Martínez, A., & Romeo, L. M. (2017). Evaluación de la mejora del proceso de enseñanza-aprendizaje mediante la integración de objetos de aprendizaje reutilizables en un curso abierto OCW. In In-Red 2017. III Congreso Nacional de innovación educativa y de docencia en red (pp. 185-194). Editorial Universitat Politècnica de València. https://doi.org/10.4995/INRED2017.2017.6847

_______________________________

*Autor de correspondencia / Corresponding author

1 The documentation of the University of Malaga’s call for innovative educational projects 2019-2021 can be consulted at: https://d66z.short.gy/HkvwQs

2 In the specific university field, a study by the Anglo-Saxon academic portal Zinch in 2012 showed that two-thirds of teenagers used social networks to compare opinions about university centres before enrolling. In particular, 42% found YouTube credible when selecting a university. See https://d66z.short.gy/MXwRMn (accessed 9 May 2019).

3 The coordinators were Laura Teruel, a tenured professor who also co-directed the previous educational innovation projects, and María Sánchez, a doctoral associate professor with extensive experience, also linked to her professional activity at the International University of Andalusia in academic innovation and networked teaching-learning.